Several archdiocesan pastors have echoed a recent call by the U.S. bishops to examine COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on African Americans.

Archbishop Nelson Perez, chairman of the bishops’ Committee on Cultural Diversity in the Church, joined leaders of three additional committees of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in a May 4 statement urging “state and local leaders to examine the generational and systemic structural conditions that make the new coronavirus especially deadly to African American communities.”

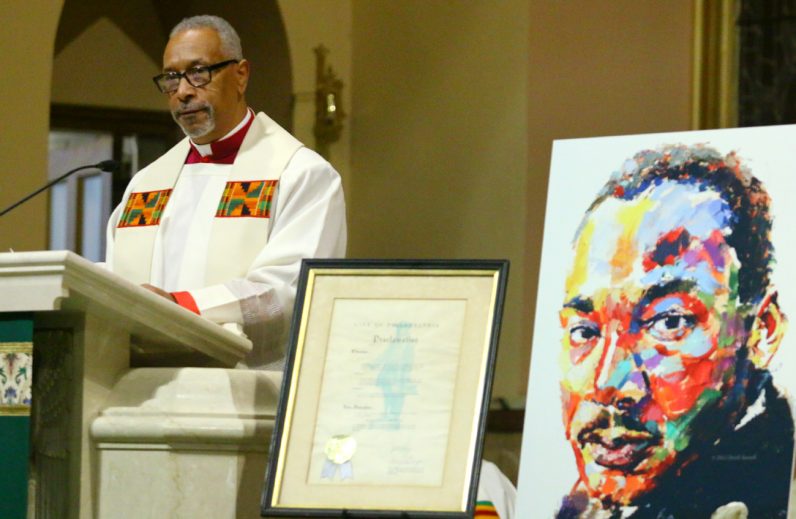

Msgr. Federico Britto, pastor of St. Cyprian and St. Ignatius parishes in Philadelphia, preaches during a Jan. 20 prayer service in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at Our Mother of Consolation Parish in Philadelphia. Msgr. Britto lost a brother to COVID-19, which also infected another brother and a sister. (Photo by Sarah Webb)

While statistics are still emerging, current data suggest that the disease has led to higher rates of hospitalization and death among African Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

For Msgr. Federico Britto, COVID-19 “hits home.”

“I lost a brother to it, and another brother and sister were also infected,” said Msgr. Britto, pastor of St. Cyprian Parish and parochial administrator of St. Ignatius of Loyola Parish, both in Philadelphia.

Noting that his siblings had previously been “healthy people” prior to contracting the virus, he stressed that “we cannot let our guard down when it comes to this disease,” he said.

‘Stay at home’ is very relative

Father Stephen Thorne, pastor of St. Martin de Porres Parish in North Philadelphia, said that COVID-19 has exacerbated the city’s longstanding problems with poverty, violence, housing and education.

“Basically, what the pandemic has done is expose what we already know,” said Father Thorne, who also serves as chaplain at Neumann University and as a consultant to the National Black Catholic Congress. “Every one of those statistics, that’s us, that’s this neighborhood.”

Even public health measures designed to counter the spread of the disease have been challenging for his parish’s largely African American neighborhood, he said.

Small houses shared by multigenerational families have made social distancing difficult, if not impossible, said Father Thorne.

“When you think about someone living in a crowded space, or in a place with domestic violence, the term ‘stay-at-home’ becomes very relative,” he said.

In addition, African Americans are overrepresented in many frontline worker positions, placing them at greater risk of contracting COVID-19. The CDC notes that 30% of all licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses in the U.S. are African American.

Close to 25% of employed African Americans are in service industry jobs for which salaries are already insufficient, paid sick leave nonexistent and public transportation — with its increased potential for COVID-19 exposure — the only option.

Father Stephen Thorne, pastor of St. Martin de Porres in North Philadelphia, leads a livestreamed liturgy on Good Friday, April 10. The coronavirus pandemic calls the church to be “on the frontline” in addressing systemic inequalities that have made African Americans more vulnerable to the disease, he said. (Photo courtesy of Father Stephen Thorne)

“A lot of people in this neighborhood have to go out and work in maintenance, in stores, in markets, even with the risk,” said Father Thorne.

Parishioners at St. Athanasius in the city’s West Oak Lane section are doing the same, said Father Joseph Okonski, pastor.

“They’re delivering mail and packages, working in grocery stores, nursing homes and hospitals,” he said. “And they’ve made it very clear they’re afraid. They put their lives in God’s hands, and pray that the Precious Blood of Our Lord covers them every time they go to work.”

One hospital worker in his parish “would love to stay at home,” but with four children and a wife who just lost her hotel-industry job, “that’s not an option,” said Father Okonski.

Although he cautioned against viewing African American communities as economically and culturally “monolithic,” Father Okonski said that many hardworking African American families in his parish live on thin financial margins that often require them to forego one critical expense to cover another.

“They have to make these kinds of choices because of low salaries,” he said. “They can’t take time off; there’s no money put aside. If something breaks down, if work doesn’t provide health insurance, they do without.”

Profits before people

Corporate negligence has placed several of his parish’s health care workers and nursing home residents at risk for the disease, said Father Okonski.

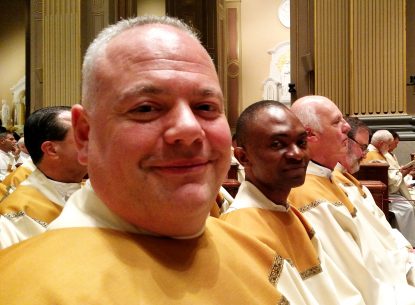

Father Joseph Okonski, pastor of St. Athanasius Church in Philadelphia’s West Oak Lane section (seen here with Redemptorist Father Anayo Nna in this undated photograph), said that many of his African American parishioners “put their lives in God’s hands” as they continue to work in jobs that place them at greater risk for contracting the coronavirus. (Photo courtesy of Father Joseph Okonski)

Many area nursing homes have been “very poor at protecting not only their residents, but their workers,” with “profits overriding the care of both,” he said.

At one nearby home, he said, a resident contracted the coronavirus, exposing a parishioner who worked there. Administrators did not alert staff, and the parishioner had to ask to be tested — a request that took three days to be fulfilled.

In response, Father Okonski alerted both health officials and the facility itself.

“We have parishioners living in there and working there,” he said. “This is unconscionable.”

Even in medical facilities with more robust safety protocols, African American health care staff can feel vulnerable, especially if they’re working in entry-level or janitorial support positions, said Father Christopher Walsh, pastor of St. Raymond of Penafort in the Stenton section of Philadelphia.

“If they’re cleaning the hospital, they feel they don’t rank like doctors and nurses, and they’re not getting PPE (personal protective equipment),” he said.

More testing needed

Several area pastors emphasized the need for widespread virus testing among African American communities, with Father Walsh suggesting that Catholic hospitals should consider organizing such initiatives in underserved areas.

Comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes and heart disease among African Americans also deserve further attention, he said.

Father Walsh is concerned with making sure his parishioners receive routine medical care.

Father Christopher Walsh, pastor of St. Raymond of Peñafort in Philadelphia, holds an infant while delivering a homily at an Oct. 24, 2019 healing prayer service at the Cathedral Basilica of SS. Peter and Paul’s chapel. Father Walsh suggested Catholic hospitals should organize COVID-19 testing in underserved areas. (Photo by Sarah Webb)

“It’s still shocking to me at times when I’m speaking to an older person, and they tell me they don’t regularly go to the doctor or even have a doctor,” he said.

Along with numerous media reports, Father Okonski stated that the number of COVID-related deaths in area nursing homes is being deliberately underreported, and that transparent data on the disease is critical.

He said that the broad array of issues raised by the coronavirus are reasons for “holding our elected officials and social services advocates accountable” in stewarding public health.

The church as frontline worker

Father Thorne said that amid the coronavirus crisis, “the church must continue to be present” in African American communities.

“We are on the front line,” he said, adding that pastors and parishioners should root themselves deeply in the life of their area neighborhood.

He said he recently went to a local supermarket “on purpose, to go through the store and stand in line … to be among the sheep and to understand” better the experiences of his congregation.

Clergy are “in the forefront of the pandemic,” said Msgr. Britto. “We pray, we visit the sick, we bury the dead, and as priests it affects us.”

With public Masses suspended, African American Catholics in the archdiocese are sustaining their faith through livestreamed liturgies, online devotions and Bible studies, and regular contact through phone calls and social media, said a number of pastors.

Noting that his parish adjoins a number of affluent neighborhoods, Father Thorne said that contingent parishes should strive to work more closely with each other to address inequalities that have aggravated the pandemic for African Americans.

Catholic education is key to forging the post-pandemic future of both the church and the community, he said.

“God is with us, and this is no time for negativity,” said Father Thorne. “We are a voice for the voiceless, and we have to be people of hope.”